Why Garlic Groups?

Genetic testing to determine inter-relationships between garlic cultivars and their placement in possible groups has been carried out in many countries. This description of garlic groups is based partly on work done by Ron L. Engeland in his book Growing Great Garlic, and on G.M. Volk et al. (2004), and is explained in depth by T.J. Meredith in The Complete Book of Garlic. These are the groupings that are used to sort and describe garlic in the USA.

However, these groupings are not universally accepted. France, for example, only recognises some of the US groups. Also, DNA research is constantly being refined and methods updated, and it is entirely possible that different groupings may be determined in the future. DNA research done by M.H. Jo et al. (2012), using different genetic markers to those used by Volk et al., has suggested that genetic diversity is correlated with geographical region. Their garlic fell into only four different Groups. Geographical variation leaves open the possibility that some of Australia’s cultivars may be distinctly different from those in the US, even if they have the same name. So perhaps they should be grouped in other ways. Only more research can determine this. Until genetic testing is done on the available Australian cultivars then the groups described below work reasonably well to explain the majority of similarities and differences in garlic cultivars available in Australia.

In the hot southern European countries like France and Spain, as well as Asian and South-American countries, the majority of garlics grown fall into four groups: those that contain the heat-loving cultivars, namely the Artichoke, Silverskin, Creole and Turban Groups. Most of the garlics found in mainland Australia also fall into these groups. In northern Europe, Canada and northern USA, you are more likely to find the strongly bolting groups like Rocamboles, Purple Stripes and Porcelains. The only parts of Australia where these groups can be easily grown are Tasmania and highland regions of the mainland’s southern states. Artichokes and Creoles will grow in hot and cold regions, and some Purple Stripes are more heat tolerant than others. Even knowing this, deciding which group an individual garlic belongs to is sometimes still a knowledgeable grower’s best guess and very much open to discussion. Sometimes they need to be grown for several years in different climate zones before they can be accurately assigned to a particular group.

Groups are important because of the many characteristics they share. If you know that a garlic is in the Turban Group, for example, you will know that it forms big bulbs with big, easy-to-peel cloves; that the flavour is hot when raw, but mild when cooked, and that you don’t have to remove the scapes because leaving them on doesn’t affect bulb size. In Australia where there is huge confusion around garlic names, if you can determine what group a garlic belongs to, you will at least have an idea of whether it will grow in your region or not, approximately when it needs to be planted and harvested, how long it will store, and what the flavour will be like. This cultivar will share these characteristics with the other cultivars in that group. Increasingly growers should be able to tell you what groups their cultivars belong to, and this too will help reduce confusion.

For example, a cultivar called Rocambole Festival is not actually in the Rocambole but in the Creole Group. So, even though it is called ‘Rocambole’, the purchaser who knows it’s in the Creole Group will therefore be aware that the clove has a hot, spicy taste rather than the complex, nutty one that is characteristic of the Rocambole Group; and will also know that it is long keeping rather than shorter keeping, and should be planted later in the season rather than mid-season.

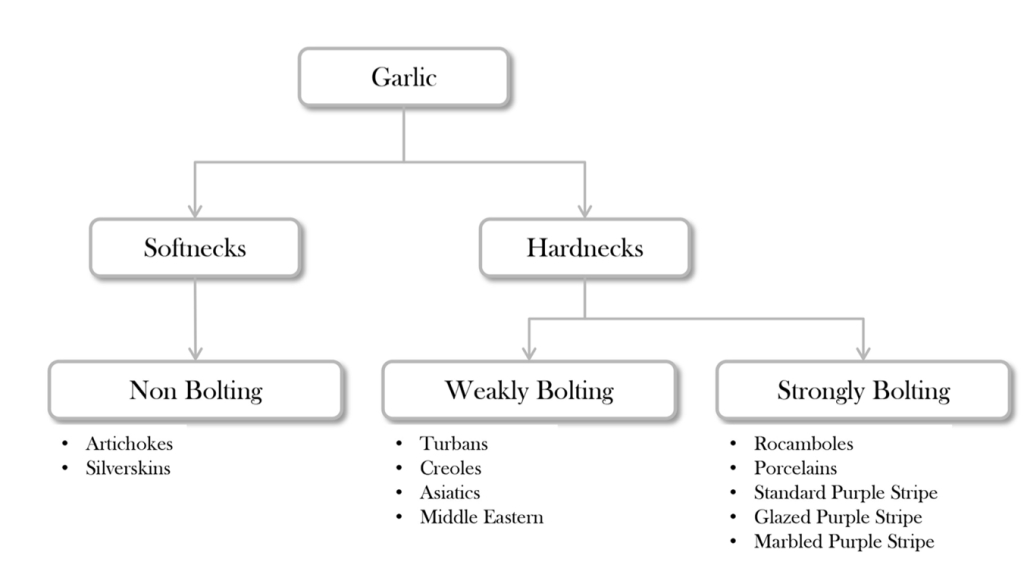

Garlic is divided into hardneck and softneck types. The hardnecks usually produce scapes, the softnecks usually don’t. Softnecks are also known as non-bolting, while hardnecks are divided into weakly bolting and strongly bolting cultivars. If a garlic is described as weakly bolting, this means it usually produces a scape, especially when stressed by cold conditions. (Sometimes drought, prolonged heavy rainfall or other stresses will have the same effect.) The corollary of this is that sometimes it might not grow a scape. This is particularly true in warmer climates. Scapes on weakly bolting plants are usually floppy and/or produce an upside-down U or S-shape. Often the scapes are not completely solid, and usually appear late in the growing cycle. Turban scapes are very typical of this. Strongly bolting cultivars produce their scapes early and very definitively. The scapes are tall, strong and solid, and create vigorous curls and twists ranging from 270° curls to curls that are 720° (2 circles) or even 1080° (3 circles). The latter are typical of garlics in the Rocambole Group.